Every year, millions of people take multiple medications - some for chronic conditions, others for temporary symptoms. What most don’t realize is that their genes might be silently making those drugs more dangerous than they should be. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening right now in clinics, pharmacies, and hospitals. And the solution isn’t just avoiding certain pills. It’s understanding pharmacogenomics - how your DNA shapes the way your body handles every drug you take.

Why Your Genes Matter More Than You Think

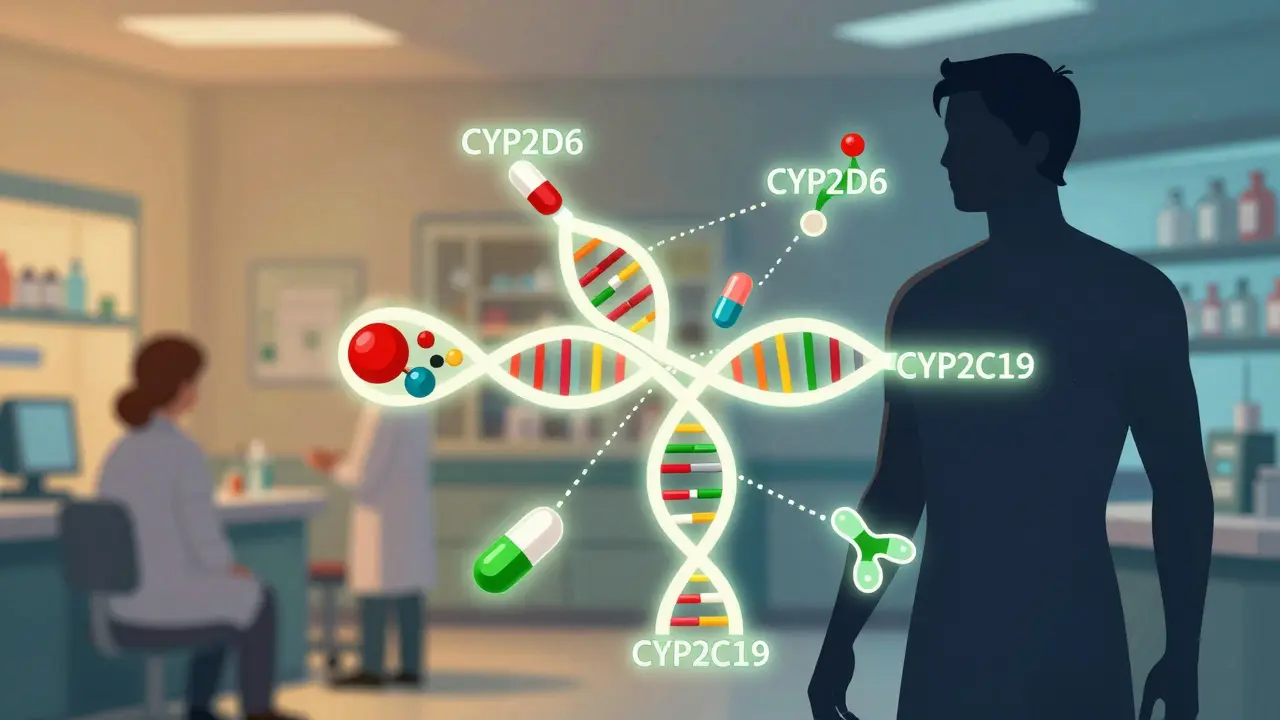

Most drug interaction checkers only look at what pills you’re taking. They don’t ask: What’s in your DNA? That’s the gap pharmacogenomics fills. Two people can take the same dose of the same drug, and one might feel fine while the other ends up in the hospital. The difference? Their genes. Take CYP2D6, one of the most important drug-metabolizing enzymes. About 7% of people of European descent are poor metabolizers - meaning their bodies break down certain drugs too slowly. If one of these people takes codeine, their body can’t convert it properly into morphine. The drug won’t work. But if they’re an ultra-rapid metabolizer - about 1-10% of people depending on ancestry - they turn codeine into morphine too fast. That can lead to dangerous opioid levels, even at normal doses. The FDA has warned about this since 2013. Yet, most prescriptions still ignore this genetic reality. The same goes for CYP2C19. People with certain variants can’t activate clopidogrel (Plavix), a common blood thinner. Without activation, the drug does nothing. In 2023, the FDA updated its label to say that patients with these variants should get an alternative. But how many doctors actually test for it? Fewer than you’d think.How Gene-Drug Interactions Turn Safe Drugs Into Risks

Drug interactions aren’t just about two pills clashing. They’re often a three-way fight: drug A, drug B, and your genes. This is called a drug-drug-gene interaction (DDGI). And it’s far more common than traditional checkers suggest. Imagine someone taking fluoxetine (Prozac) and metoprolol (a beta-blocker). Fluoxetine blocks CYP2D6 - a major enzyme that breaks down metoprolol. If the patient is already a poor CYP2D6 metabolizer, this combo can cause metoprolol to build up to toxic levels. That’s two hits: one from the drug interaction, one from the genetics. A standard drug interaction checker might flag the fluoxetine-metoprolol combo. But it won’t know if the patient’s genes make the risk 10 times worse. A 2022 study in the American Journal of Managed Care found that when genetic data was added to standard interaction screens, the estimated risk of serious interactions jumped by 90.7%. Antidepressants, antipsychotics, and pain meds were the top culprits. Why? Because they’re often metabolized by just a few key enzymes - CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9 - and small genetic differences have huge effects. Even more surprising? Drugs can temporarily change your genetic phenotype. This is called phenoconversion. For example, if you’re an ultra-rapid metabolizer but take a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor like paroxetine, your body suddenly behaves like a poor metabolizer. Your genes didn’t change - but your body’s ability to process drugs did. Standard interaction tools can’t predict this. Only pharmacogenomics can.The Real Cost of Ignoring Genetics

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are the fourth leading cause of death in the U.S. - ahead of pneumonia and diabetes. They cost the healthcare system over $30 billion a year, according to a 2019 study in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. Many of these aren’t random accidents. They’re predictable, genetically driven events. Take azathioprine, used for autoimmune diseases. If you have a TPMT gene variant that reduces enzyme activity, your body can’t break down the drug. Standard doses cause severe bone marrow damage. The FDA says poor metabolizers need just 10% of the usual dose. But without testing, doctors have no way of knowing. In 2021, a study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics found that 1 in 300 people had this variant - and most didn’t know it until they had a life-threatening reaction. Another example: carbamazepine. If you carry the HLA-B*15:02 allele - common in people of Southeast Asian descent - your risk of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (a deadly skin reaction) skyrockets. The FDA requires testing before prescribing in high-risk populations. But in places without routine genetic screening, patients still get the drug and suffer. These aren’t rare edge cases. They’re systemic failures. And they’re avoidable.

What’s Being Done - And What’s Still Missing

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) has been publishing guidelines since 2009. As of 2023, they’ve covered over 100 drug-gene pairs. These aren’t opinions. They’re based on clinical trials, FDA labels, and peer-reviewed evidence. For example, CPIC says: if you’re a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer taking clopidogrel, switch to prasugrel or ticagrelor. Simple. Clear. Life-saving. Some institutions are ahead of the curve. Mayo Clinic has been doing preemptive PGx testing since 2011. They’ve tested over 100,000 patients. Their system flags dangerous combinations in real time - and doctors follow the alerts 85% of the time. The result? A 45% drop in inappropriate prescribing. But most hospitals? Still flying blind. Only 15% of U.S. healthcare systems have PGx results built into their electronic records. Community pharmacies? Even worse. A 2023 survey found only 28% of pharmacists felt trained to interpret PGx results. And 67% said they had no decision support tools to help them. The tools exist. The data exists. But the infrastructure doesn’t. Most labs don’t standardize how they report phenotypes. One lab might call a patient a “moderate metabolizer,” another says “intermediate.” There’s no universal language. That’s dangerous.The Future Is Here - But Only for Some

The global pharmacogenomics market is growing fast - projected to hit $24 billion by 2030. Companies like 23andMe now offer limited PGx reports to over 12 million customers. But here’s the catch: those reports are for informational use only. They don’t replace clinical testing. And they’re not designed for complex polypharmacy cases. The NIH’s All of Us program has returned PGx results to over 250,000 people. That’s a huge step. But the data isn’t evenly distributed. Only 2% of participants in PGx studies are of African ancestry. That means the guidelines we have today may not work for everyone. A variant common in African populations might be missing from the FDA’s list. That’s not just a scientific gap - it’s a health equity crisis. Artificial intelligence is starting to help. A 2023 study in Nature Medicine showed an AI model that included PGx data improved warfarin dosing accuracy by 37%. Warfarin is tricky - it’s affected by CYP2C9, VKORC1, and multiple drugs. Traditional dosing tools get it wrong half the time. AI with genetics? It’s much closer to perfect.

Ellie Stretshberry

December 26, 2025 AT 20:58i had no idea my genes could make my meds dangerous

my doc just kept upping my dose when i felt worse

turns out i’m a slow metabolizer for cyp2d6

now i’m on a different pill and i actually sleep at night

Zina Constantin

December 27, 2025 AT 18:35This is the most important medical breakthrough most people have never heard of. Imagine if we screened for blood type before giving transfusions - that’s where we are with pharmacogenomics. It’s not futuristic. It’s foundational. We’re still treating patients like lab rats instead of individuals with unique biology. The FDA knows. CPIC knows. Why aren’t we all doing this yet?

Dan Alatepe

December 28, 2025 AT 07:20bro this is wild 🤯

my aunt died from a drug reaction and no one ever checked her dna

now i’m scared to even take tylenol

why is this not on every prescription like a warning label??

Angela Spagnolo

December 30, 2025 AT 05:32I just read this... and I’m crying? Not because it’s sad, but because it’s so obvious... and yet, no one talks about it. I’ve been on 7 meds for 5 years. Three of them didn’t work. Two gave me nightmares. I thought it was me. Turns out... maybe it was my genes. I’m scheduling a test tomorrow. Please, if you’re on multiple drugs - ask. Just ask.

josue robert figueroa salazar

December 31, 2025 AT 01:00so we’re blaming genes now? not doctors? not pharma? classic.

david jackson

December 31, 2025 AT 18:39Let me just say - this isn’t just about codeine or clopidogrel. This is about the entire medical system being built on averages. The average person doesn’t exist. The average metabolism doesn’t exist. The average response to a drug? A myth. We’re prescribing based on population curves while ignoring the actual human in front of us. And when they crash? We say ‘unpredictable reaction.’ No. It’s predictable. We just refuse to look at the data. The data is right there - in the DNA. We’re choosing ignorance because it’s cheaper than changing the system.

Jody Kennedy

January 2, 2026 AT 06:17My mom’s on warfarin. She almost bled out last year. They finally tested her and found she’s a CYP2C9 slow metabolizer. They cut her dose in half. She’s fine now. Why did it take a near-death experience to get this done? I’m pushing my whole family to get tested. It’s $150. It could save your life.

christian ebongue

January 3, 2026 AT 03:32lol the system’s broken but 23andme’s ‘pharmacogenomics report’ is gonna fix it? sure. also i got flagged as a cyp2d6 ultra-rapid but my doc laughed. guess i’ll keep taking codeine and hoping for the best.

jesse chen

January 3, 2026 AT 08:20Thank you for writing this. I work in a pharmacy and we just got our first PGx integration tool last month. It’s not perfect. The reports are messy. But yesterday, I caught a combo that would’ve killed someone - fluoxetine + metoprolol + CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. We called the doctor. They switched the med. That’s one life. Imagine if every pharmacy had this. Imagine if every doctor cared.

Joanne Smith

January 4, 2026 AT 20:41They call it precision medicine. I call it ‘finally paying attention.’ I’ve been screaming about this since my cousin got hospitalized from a ‘normal’ dose of antidepressant. Turns out, she had two high-risk variants. No one asked. No one tested. Now I’m the family’s unofficial PGx advocate. I print out PharmGKB reports and hand them to relatives before their next appointment. It’s annoying. It’s necessary.