Every time you take an antibiotic when you don’t need it, you’re not just helping yourself-you’re helping bacteria become stronger. That’s the uncomfortable truth behind antibiotic resistance, a quiet crisis that’s already killing over a million people a year worldwide. It’s not science fiction. It’s happening now, in hospitals, farms, and even your own medicine cabinet.

How Bacteria Outsmart Antibiotics

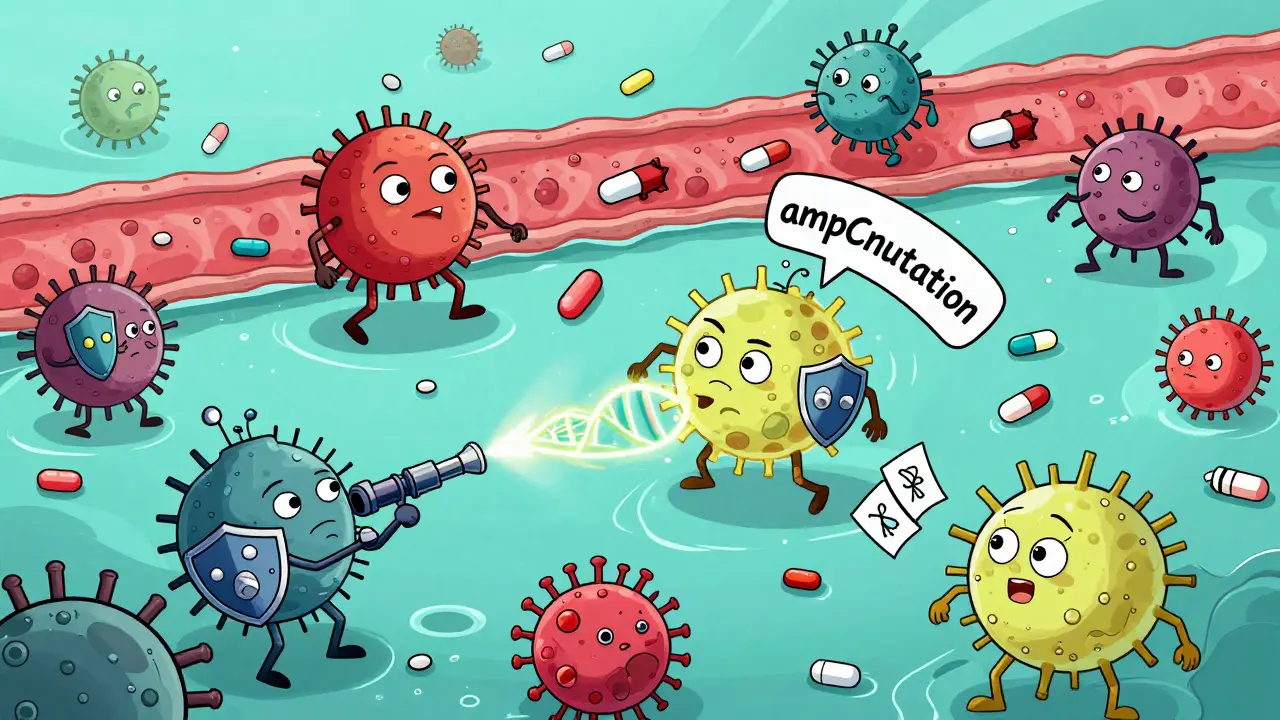

Antibiotics don’t kill bacteria because they’re powerful chemicals. They kill because they target specific weak points in bacterial cells-like the walls they build, the proteins they need to multiply, or the machinery they use to copy their DNA. But bacteria don’t sit still. They evolve. Fast.When antibiotics are around, the bacteria that happen to have a mutation that lets them survive-say, a tweak in a gene that pumps the drug out or changes the drug’s target-live on. They multiply. Their offspring inherit that advantage. Over time, the whole population shifts. What was once a harmless bug becomes a superbug.

Research shows resistance doesn’t come from one big mutation. It’s a series of small, step-by-step changes. In one study, six types of bacteria exposed to slowly increasing antibiotic doses developed resistance so strong they needed 6 times more drug to kill them. And it wasn’t random. Each type followed a pattern: ampC gene mutations for amoxicillin resistance, pbp mutations for cefepime. These aren’t guesses-they’re documented in genome sequences from real lab experiments.

Some mutations are quick but temporary. Bacteria can change how their genes are turned on or off using chemical tags on their DNA-like flipping a switch. This is called methylation. It gives them a short-term shield. But if the pressure stays, they lock in the change with permanent DNA mutations. That’s when resistance becomes permanent.

And it’s not just one gene. A single bacterium can accumulate dozens of mutations. In one case, a strain of Yersinia enterocolitica picked up so many changes that it barely survived on its own. But it could still survive antibiotics. Evolution doesn’t care about fitness-it cares about survival.

It’s Not Just Antibiotics

You might think only antibiotics cause resistance. But that’s not true. A 2025 study in Nature found that common non-antibiotic drugs-like antidepressants, antihistamines, and even some painkillers-can make it easier for bacteria to grab resistance genes from their neighbors. These drugs don’t kill bacteria, but they stress them. And stressed bacteria are more likely to swap DNA.This is called horizontal gene transfer. It’s like bacteria sharing cheat codes. One bug picks up a resistance gene from another, even if they’re totally different species. That’s how a harmless gut bacterium can end up with the same gene that makes MRSA deadly. And it’s happening everywhere-in water, soil, food, and hospitals.

Even the way we give antibiotics matters. For tetracycline, resistance doesn’t come from a mutation in the pump that kicks the drug out. It comes from a mutation that breaks the gene that normally keeps that pump turned off. A tiny error in a control switch lets the pump run nonstop. That’s how a population goes from sensitive to resistant in just 150 generations-sometimes less than a month in a human body.

Why We’re Losing the Battle

The biggest driver of resistance? Misuse. In the U.S., about 30% of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions-roughly 47 million a year-are unnecessary. That’s for colds, flu, sinus infections that are viral, not bacterial. Antibiotics don’t work on viruses. But they’re still prescribed anyway.In Europe, antibiotic resistance causes 33,000 deaths a year and costs €1.5 billion in healthcare and lost productivity. In low-income countries, the problem is worse because antibiotics are sold over the counter without prescriptions. People take them for fevers, for coughs, for anything that feels wrong. And they don’t finish the course. That’s a double hit: it kills the weak bacteria, but leaves the strong ones alive to multiply.

Meanwhile, the pipeline for new antibiotics is drying up. Of the 67 antibiotics currently in development, only 17 target the most dangerous superbugs. Just three are truly new-designed to bypass existing resistance. Most are tweaks of old drugs. Bacteria have already seen those before.

What ‘Appropriate Use’ Really Means

Appropriate use isn’t just about not taking antibiotics when you don’t need them. It’s about using them right when you do.- Don’t demand antibiotics for a cold. If your doctor says you have a virus, trust them. Ask about symptom relief instead.

- Take the full course. Even if you feel better, stop early and you leave behind the toughest survivors.

- Never share or use leftover antibiotics. The dose, duration, and type are tailored to a specific infection. Using them for something else is dangerous.

- Ask about testing. For serious infections, doctors can now use rapid tests to tell if it’s bacterial or viral before prescribing.

- Support stewardship programs. Hospitals and clinics with formal antibiotic stewardship programs reduce inappropriate use by 20-30% without harming patient outcomes. These programs take 12-18 months to show results-but they work.

It’s not just about doctors and patients. Farmers use antibiotics to make livestock grow faster, not to treat illness. That’s a major source of resistant bacteria entering the food chain. Many countries have banned this, but not all. Choosing meat raised without routine antibiotics helps reduce the spread.

What’s Being Done-And What’s Not

The World Health Organization calls antimicrobial resistance one of the top 10 global health threats. 150 countries have national plans to fight it. But only 75% of high-income nations are actually carrying them out. In low-income countries, it’s around 35%.Scientists are exploring wild new ideas: CRISPR tools that cut resistance genes out of bacteria, drugs that block bacterial communication, or even phage therapy-using viruses that kill bacteria. But these are still experimental. None are widely available yet.

The FDA recently updated testing standards for cefiderocol, a last-resort antibiotic, to better track resistance in carbapenem-resistant bacteria. That’s progress. But it’s reactive. We’re always playing catch-up.

The real solution? Prevention. Slowing resistance means reducing unnecessary use everywhere-hospitals, farms, homes. It means investing in rapid diagnostics so doctors don’t guess. It means global cooperation. Resistance doesn’t respect borders.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to be a scientist to help. Here’s what works:- Get vaccinated. Flu shots, pneumococcal vaccines, and others prevent infections that might otherwise lead to unnecessary antibiotic use.

- Wash your hands. Simple, effective, and stops the spread of resistant bugs.

- Ask questions. If you’re prescribed an antibiotic, ask: "Is this definitely bacterial? Are there alternatives? What happens if I don’t take it?"

- Dispose of old antibiotics properly. Don’t flush them. Take them to a pharmacy drop-off.

- Support policies that limit antibiotic use in agriculture. Vote, speak up, choose brands that don’t use them routinely.

Antibiotic resistance isn’t inevitable. It’s a human-made problem. And that means it can be fixed-with the right choices, at every level.

Can antibiotic resistance be reversed?

Yes, but slowly. If you stop using an antibiotic, the resistant strains often lose their advantage because the mutations that give resistance usually make bacteria less efficient at growing or competing. Over time, sensitive strains can come back. But this doesn’t happen overnight-it can take years. And if the resistance gene is carried on a plasmid (a piece of movable DNA), it can spread to other bacteria even without antibiotics present. So reducing use helps, but it’s not a quick fix.

Do probiotics help prevent antibiotic resistance?

No. Probiotics may help with side effects like diarrhea during antibiotic treatment, but they don’t stop resistance from developing. In fact, some probiotic strains carry their own resistance genes. They’re not a shield against superbugs. The best way to prevent resistance is to use antibiotics only when necessary and as directed.

Are natural remedies like honey or garlic effective against resistant bacteria?

Some natural substances, like medical-grade honey, have shown antibacterial properties in lab settings and are used in wound care under supervision. Garlic has compounds that can slow bacteria in test tubes. But none have been proven to treat serious infections caused by resistant bacteria in humans. Relying on them instead of antibiotics can be dangerous. They’re not replacements for proven medical treatment.

Why don’t we just make new antibiotics?

It’s expensive and hard. Developing a new antibiotic costs over $1 billion and takes 10-15 years. Most new drugs are minor changes to old ones, which bacteria quickly overcome. Pharmaceutical companies focus on chronic diseases like diabetes or cancer because they’re more profitable. Antibiotics are used for short periods, so they don’t generate the same revenue. Without government incentives, companies won’t invest.

Can I get resistant bacteria from my pet?

Yes. Pets can carry resistant bacteria from their food, environment, or from being treated with antibiotics. These can spread to humans through direct contact or contaminated surfaces. Always wash your hands after handling pets, especially if they’re sick or on antibiotics. Don’t give your pet human antibiotics-they’re dosed wrong and can cause resistance in their microbiome.

What Comes Next

The clock is ticking. Without major changes, we risk entering a post-antibiotic era-where simple infections like strep throat or a scraped knee could become deadly again. The World Bank estimates uncontrolled resistance could push 24 million people into extreme poverty by 2050.But we’re not powerless. Every time you choose not to take an antibiotic for a virus, every time you finish your prescription, every time you ask your doctor why it’s needed-you’re part of the solution. Antibiotic resistance isn’t just a medical problem. It’s a social one. And fixing it starts with awareness, responsibility, and action-starting today.

Dusty Weeks

January 2, 2026 AT 15:29Bryan Anderson

January 3, 2026 AT 04:23Sally Denham-Vaughan

January 5, 2026 AT 02:04Matthew Hekmatniaz

January 6, 2026 AT 17:51Paul Ong

January 7, 2026 AT 07:36Liam George

January 7, 2026 AT 23:41sharad vyas

January 8, 2026 AT 22:29Richard Thomas

January 9, 2026 AT 10:20Bill Medley

January 10, 2026 AT 16:02Todd Nickel

January 11, 2026 AT 03:58Andy Heinlein

January 11, 2026 AT 05:08Ann Romine

January 12, 2026 AT 13:36Austin Mac-Anabraba

January 14, 2026 AT 12:10