When a generic drug hits the shelf, how do we know it works just like the brand-name version? It’s not guesswork. It’s science - and at the heart of that science are two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just lab jargon. They’re the gatekeepers of safety and effectiveness for every generic medicine you take.

What Cmax and AUC Actually Measure

Cmax stands for maximum concentration. It’s the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after you swallow it. Think of it like the peak of a wave - how high the drug climbs before it starts to drop. This matters because for some medicines, like painkillers or antibiotics, the effect kicks in hardest right at that peak. If the generic version doesn’t hit the same high, you might not get the relief you need.

AUC - area under the curve - tells you something different. It’s the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time. Imagine drawing a graph of drug levels in your blood from the moment you take the pill until it’s completely gone. The area under that line? That’s AUC. It tells you how much medicine your body has absorbed overall. For drugs that need to build up over time - like blood thinners or antidepressants - AUC is the key to making sure you’re getting enough, not too little, not too much.

These aren’t abstract concepts. In real studies, a brand-name drug might show a Cmax of 8.1 mg/L and an AUC of 124.9 mg·h/L. A generic version might show 7.6 mg/L and 112.4 mg·h/L. That’s a 90% match. And that’s considered good enough.

Why Both Numbers Matter - Not Just One

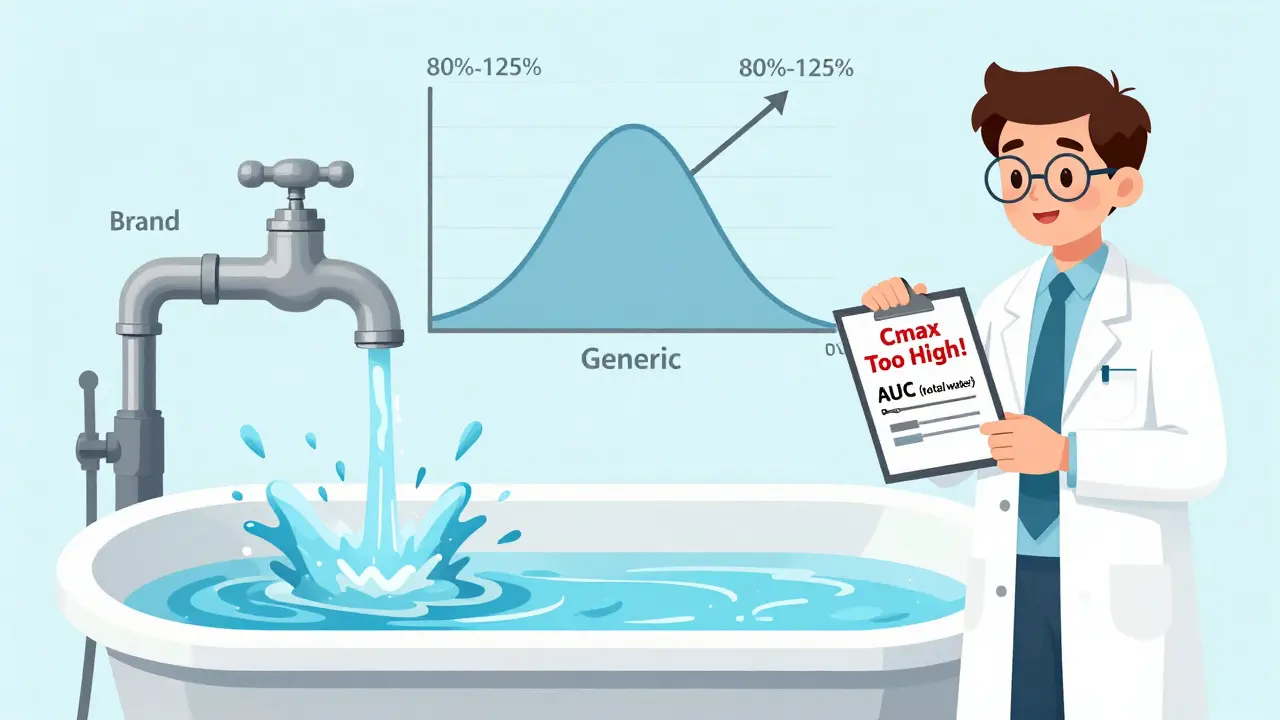

You might think: if the total exposure (AUC) is the same, why care about the peak? But here’s the catch: two drugs can have the same AUC but very different Cmax values. One could spike fast and high, the other rise slowly and stay steady. That’s not the same thing.

Take a drug like warfarin, used to prevent blood clots. Too much too fast can cause dangerous bleeding. Too little won’t protect you. If a generic version spikes higher than the brand (even if total exposure is the same), it could push you into a risky zone. That’s why regulators don’t just check AUC - they demand both Cmax and AUC meet the standard.

It’s like filling a bathtub. AUC is how much water ends up in the tub. Cmax is how fast it fills. If you turn the tap on full blast, the tub fills fast - but the water pressure might burst the pipes. If you let it drip slowly, it takes longer, but it’s safe. Both ways can fill the tub, but only one is safe for your plumbing. Your body is the plumbing.

The 80%-125% Rule: How Close Is Close Enough?

Regulators don’t say “must be identical.” They say: “must be close enough that it won’t change how the drug works.” That’s where the 80%-125% rule comes in.

For both AUC and Cmax, the ratio of the generic to the brand must fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand’s AUC is 100, the generic’s has to be between 80 and 125. Same for Cmax.

This range isn’t arbitrary. It comes from decades of data and statistical analysis. In 1991, experts at the BioInternational conference reviewed thousands of drug studies and found that differences smaller than 20% rarely affected how patients felt or how safe the drug was. That’s why 80%-125% became the global standard.

And here’s the kicker: both values must pass. If AUC is 95% but Cmax is 75%, the drug fails. No exceptions. That’s because one can’t make up for the other. Your body cares about both how much it gets and how fast it gets it.

How These Numbers Are Measured - And Why It’s Tricky

Getting accurate Cmax and AUC isn’t easy. It takes blood samples - often 12 to 18 times over 24 to 72 hours - after someone takes the drug. The timing has to be perfect. If you miss the exact moment the drug peaks, your Cmax is wrong. And if you don’t sample long enough, your AUC is too low.

Studies are usually done on healthy volunteers in a crossover design: they take the brand one week, then the generic the next, with a washout period in between. This removes individual differences - one person’s metabolism won’t skew the results.

Modern labs use ultra-sensitive tools like LC-MS/MS to detect drug levels as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. That’s a drop in a swimming pool. But even with this tech, poor sampling during the first 1-2 hours is the #1 reason bioequivalence studies fail. You can’t measure a peak if you didn’t catch it.

And the data? It’s not analyzed as-is. Because drug concentrations follow a log-normal pattern (not a straight line), the numbers are converted to logarithms before comparison. This isn’t just math - it’s necessary to get accurate, reliable results.

When the Rules Get Tighter - Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Not all drugs are created equal. Some have a very narrow window between working and causing harm. Warfarin, lithium, levothyroxine, and phenytoin are examples. A 10% difference in exposure can mean the difference between a seizure and a stroke.

For these, the standard 80%-125% rule is too loose. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the FDA now recommend tighter limits - 90% to 111% - for certain drugs in this category. Some regulators even require additional studies or real-world outcome data to approve them.

It’s not about distrust. It’s about caution. If a drug can kill you if you’re off by a little, you don’t take chances. That’s why generics for these drugs often cost more and take longer to get approved.

What Happens When a Generic Fails Bioequivalence?

If a generic doesn’t meet the AUC and Cmax criteria, it doesn’t get approved. Period. Companies don’t get a second try unless they reformulate - change the coating, the filler, the manufacturing process. That can cost millions and delay the drug’s release by years.

And it happens more than you think. Industry data shows about 15% of bioequivalence studies fail because of poor sampling or flawed design - not because the drug is bad, but because the test didn’t capture the real picture.

That’s why regulators insist on strict protocols. Every blood draw, every time point, every statistical method has to be documented. There’s no room for shortcuts.

Why This System Works - And Why It’s Here to Stay

Over 1,200 generic drugs were approved in the U.S. in 2022 alone. Nearly all of them relied on AUC and Cmax data. And here’s the proof it works: a 2019 analysis of 42 studies in JAMA Internal Medicine found no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness between generics and brand-name drugs that passed bioequivalence testing.

Even with new technologies like modeling and simulation on the horizon, experts agree: AUC and Cmax aren’t going anywhere. They’ve been validated for over 30 years. Used in more than 120 countries. Trusted by regulators, doctors, and patients.

It’s simple: if two pills deliver the same total exposure and the same peak concentration, they’ll do the same job in your body. That’s the foundation of affordable, safe medicine.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence?

For complex drugs - like slow-release pills that release medicine in stages - AUC and Cmax aren’t enough. A single peak doesn’t capture multiple absorption waves. That’s why the FDA is now looking at partial AUC (measuring exposure during specific time windows) for these products.

But for the vast majority of pills you take - the antibiotics, the blood pressure meds, the pain relievers - Cmax and AUC are still the gold standard. They’re not perfect, but they’re proven. And right now, they’re the only thing standing between you and a generic drug that might not work.

Michael Marchio

January 10, 2026 AT 09:44Cmax and AUC aren't just numbers-they're the invisible hand that keeps your meds from turning your body into a science experiment. I've seen studies where generics passed AUC but failed Cmax, and patients ended up with wild swings in symptoms. One guy on warfarin thought he was fine until his INR spiked after switching to a generic that peaked too fast. No one told him the peak mattered. Regulators know this. That's why they demand both. It's not bureaucracy-it's damage control.

Lisa Cozad

January 10, 2026 AT 13:02I work in pharmacy and see this every day. Patients assume 'generic = cheaper = worse.' But the data doesn't lie. I've had people come in scared after switching, convinced their blood pressure med stopped working. We pull up the bioequivalence report, show them the 92% Cmax and 98% AUC, and their whole demeanor changes. It's not magic. It's math. And math doesn't care about brand names.

Christine Milne

January 11, 2026 AT 01:43While I appreciate the technical precision of this post, I must emphasize that the FDA's 80%-125% threshold is a gross oversimplification rooted in 1980s statistical convenience, not biological necessity. In Europe, the EMA has already begun mandating individualized pharmacokinetic profiles for high-risk generics. The U.S. is clinging to an outdated paradigm that prioritizes cost-efficiency over patient-specific variability. This is not science-it is regulatory inertia masquerading as rigor.

Jay Amparo

January 11, 2026 AT 11:29Let me tell you something-I grew up in a village where people took generics because that’s all they could afford. But they didn’t just take them-they trusted them. Why? Because the doctors, the pharmacists, the regulators-everyone made sure those pills worked. Cmax and AUC? They’re the quiet heroes behind every cheap antibiotic that saved a kid’s life. No flashy ads. No brand logos. Just science doing its job. And honestly? That’s beautiful.

Ashlee Montgomery

January 13, 2026 AT 04:01If two drugs have the same AUC but different Cmax, are they really the same? Or are we just pretending equivalence is a binary state when biology is a spectrum? We measure what we can, not what we know. The bathtub analogy helps-but what if the pipes are different? What if the water pressure changes with age, diet, liver function? We’re reducing a living system to two numbers. That’s not bad. It’s just incomplete.

Jake Nunez

January 14, 2026 AT 07:38My uncle took a generic for his thyroid and ended up in the ER. They said it was bioequivalent. Turns out the filler changed how fast it dissolved. He didn't know. The pharmacist didn't know. The system didn't catch it. Cmax matters. Always. Don't let the numbers make you feel safe if your body's screaming otherwise.

McCarthy Halverson

January 15, 2026 AT 13:54Don't forget the sampling window. If you miss the first two hours you're basically guessing Cmax. I've seen studies fail because they didn't sample at 0.5h or 1h. It's not the drug-it's the method. And that's why the FDA insists on strict protocols. It's not about being rigid. It's about not lying to patients.

Ian Cheung

January 16, 2026 AT 08:52That 80-125 rule is genius really. It’s not about perfection it’s about safety buffer. Like letting your car idle for 30 seconds before driving in winter. You don’t need to warm it up to 98.6 degrees just to get going. Just enough. And if your drug’s peak is 78% of the brand? Yeah that’s a red flag. But 81%? That’s fine. Your body’s got room to breathe. And so should the system.

neeraj maor

January 17, 2026 AT 01:28They say AUC and Cmax are gold standard. But who owns the labs? Who funds the studies? Big pharma. The brand-name companies pay for the bioequivalence tests. The same companies that sued to block generics for 20 years. The numbers are manipulated. The sampling windows are rigged. The 'healthy volunteers' are paid students who don't metabolize like real patients. This isn't science. It's a cover. And you're all drinking the Kool-Aid.

Jake Kelly

January 17, 2026 AT 16:51For all the complexity, the bottom line is simple: if a generic passes Cmax and AUC, it’s safe. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t get sold. No exceptions. No lobbying. No loopholes. That’s why generics work. Not because they’re cheap. Because they’re checked. And that’s worth more than any brand name.