Ever picked up a prescription and wondered why the pill has three different names? You might see propranolol on the label, but your doctor called it by a brand name like Inderal. And if you dug deeper, you’d find a mouthful like 1-(isopropylamino)-3-(1-naphthyloxy) propan-2-ol - that’s the chemical name. It’s not a typo. It’s not marketing fluff. It’s science, regulation, and safety all rolled into one system.

Why Do Drugs Have So Many Names?

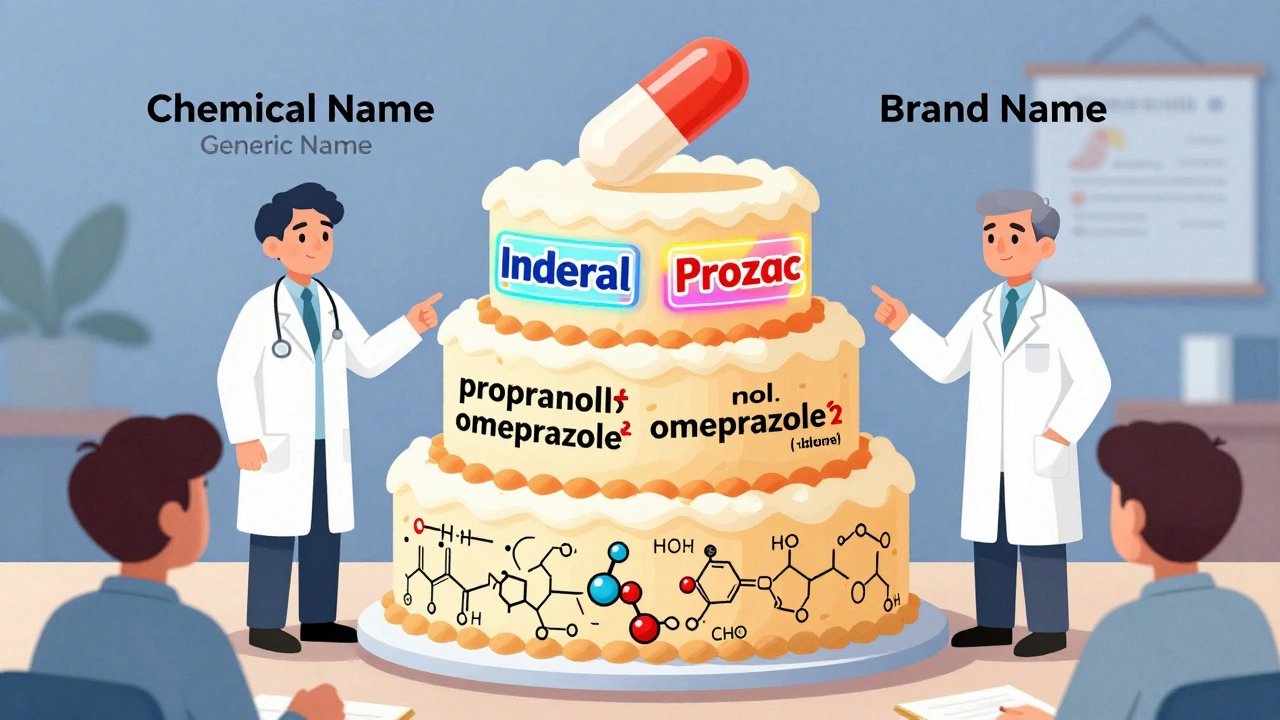

Drugs don’t get their names by random chance. There’s a strict, global system behind every label. Think of it like a three-layer cake: the bottom layer is the chemical name - precise, scientific, and useless in a pharmacy. The middle layer is the generic name - the one doctors and pharmacists use every day. The top layer is the brand name - the one you see on TV ads. Each serves a different purpose, but they all work together to keep you safe.

The system started in 1953 when the World Health Organization created the International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Programme. Before that, the same drug could have 20 different names in different countries. A patient in Tokyo might get one version, while someone in Berlin got another - and they were the exact same medicine. That’s how errors piled up. Now, over 10,000 drugs have standardized names, and about 200 new ones are added each year.

The Chemical Name: What’s Inside the Molecule

This is the drug’s DNA written in chemistry language. It tells you exactly how atoms are bonded together. For example, propranolol’s chemical name is 1-(isopropylamino)-3-(1-naphthyloxy) propan-2-ol. That’s 50 characters long. Try saying that in a busy ER. Good luck.

Chemical names follow rules set by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). They’re precise, but they’re not meant for humans. Pharmacists don’t write them on scripts. Nurses don’t chant them during rounds. They’re for chemists, patent lawyers, and regulatory filings. You’ll never see this name on a bottle - unless you’re reading the fine print on the box.

The Generic Name: The Universal Language of Medicine

This is the name that matters most. It’s the one your doctor writes, your pharmacist dispenses, and your insurance company pays for. Generic names are designed to be clear, consistent, and safe. And they follow a clever pattern.

Look at this group: omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole. All end in -prazole. That’s not a coincidence. The suffix tells you it’s a proton pump inhibitor - a drug that reduces stomach acid. The first part - ome-, lan-, pan- - is unique to each drug. It’s like a first name. The suffix is the last name, showing the family.

Same goes for imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib. The -tinib ending means it’s a tyrosine kinase inhibitor - a cancer drug that blocks specific signals in cells. Tofacitinib? That -citinib ending says it’s a JAK inhibitor, used for autoimmune diseases.

The U.S. Adopted Names (USAN) Council and WHO’s INN team work together to make sure these names don’t sound like other drugs. They reject about 30% of proposed names because they could be confused. One rejected name sounded too much like glipizide - a diabetes drug. Imagine someone mixing those up. That’s why they test names against 15,000 existing drugs using AI tools now.

Generic names also avoid medical terms. You won’t see hypertensionin or diabetol. Why? Because a drug might be approved for more than one condition later. If the name says it’s for high blood pressure, but then it’s found to help with migraines too, the name doesn’t lock it in.

The Brand Name: Marketing Meets Medicine

Here’s where things get flashy. Brand names are chosen by pharmaceutical companies. They want something catchy, easy to remember, and trademarkable. But they can’t just pick anything. The FDA reviews every single proposed brand name.

Companies submit 150 to 200 names for each new drug. The FDA’s Medication Errors team screens them for risks. About one in three get rejected. Why? If it looks like Glucotrol but sounds like Glucophage, that’s a problem. If it’s spelled like Hyzaar but pronounced like Hypertensin, it’s a red flag.

The FDA also bans names that imply results. No InstantCure or QuickRelief. No claims. No hype. Just a name that doesn’t trick you.

And here’s something most people don’t realize: brand-name drugs and generics have the same active ingredient. Same dose. Same strength. Same way it’s taken - pill, injection, patch. The only differences? The color, shape, flavor, and inactive ingredients like fillers or dyes. That’s why a generic version of Prozac might be blue and oval, while the brand is green and capsule-shaped. It’s not about effectiveness. It’s about trademarks.

But that’s also where errors creep in. In 2022, the FDA logged 347 medication errors linked to differences in pill appearance between brand and generic versions. A patient used to a blue pill suddenly gets a white one - and thinks it’s the wrong drug. Pharmacists know this. They train for it. But patients? They’re often left guessing.

Company Codes: The Hidden Numbers Before the Name

Before a drug even gets a generic name, it has a code. Pfizer uses PF-04965842-01. AbbVie uses ABBV-383. These aren’t random. The prefix stands for the company. The numbers identify the molecule. The last digits? Those are salt forms or batches.

This is the drug’s birth certificate. It’s used in labs, clinical trials, and patent filings. It’s never meant for public use. But if you ever see a number like this in a research paper, now you know what it means.

How the Whole System Works - From Lab to Pharmacy

The naming process starts early - during preclinical testing. That’s when the company assigns the internal code. By Phase I clinical trials (usually two years in), they start working with the USAN and WHO teams to pick a generic name. That takes 12 to 18 months. Then, during Phase III, they pitch brand names to the FDA. Approval comes about six to 12 months before launch.

That means from the first test tube to the first pill on the shelf, naming takes 4 to 7 years. And it’s not just paperwork. It’s safety engineering.

New Drugs, New Rules

Science doesn’t stop - and neither does naming. In 2023, the WHO introduced new stems for RNA-based drugs (-siran) and peptide-drug conjugates (-dutide). Why? Because old rules didn’t fit new science. RNA therapies are a different kind of medicine. They need their own naming family.

And then there’s targeted protein degraders - a new class of drugs that break down bad proteins in cells. Experts predict their stem will be -tecan. By 2030, this group could make up nearly 5% of all new drugs.

The USAN Council now uses AI to scan every proposed name against all existing ones. It checks spelling, sound, and even how it looks when handwritten. In its first year, this system cut confusion risks by 42%. That’s not just tech - that’s saved lives.

Why This Matters to You

You might think, “I just want my medicine to work.” And it does. But behind that pill is a system built to stop mistakes. A mistake in naming can mean a wrong dose, a bad reaction, or even death.

Studies show that standardized generic names reduce medication errors by 27%. The WHO says global harmonization has cut international errors by 18.5% since 2010. That’s not a small win. That’s thousands of people avoiding harm.

Still, 68% of patients say they find generic names confusing. That’s understandable. Tofacitinib isn’t easy to say. But it’s designed to be clear to professionals. And if you’re ever unsure, ask your pharmacist. They know the system. They’ve seen the mistakes. They can tell you what the name means - and why it matters.

What’s Next?

The system isn’t perfect. Biologics, gene therapies, and cell treatments are harder to name. Their structures are complex. Their effects are subtle. But the rules are evolving. The FDA now requires every new drug application to include a full nomenclature safety report - analyzing 12 linguistic risks.

That’s how seriously this is taken. Because when a name is wrong, someone can die. And when it’s right, millions stay healthy.

Marvin Gordon

December 5, 2025 AT 17:37Been taking generic propranolol for years and never knew the chemical name was that long. Just glad it works. My pharmacist once joked it’s the only thing longer than my wait time at CVS.

Mark Curry

December 7, 2025 AT 15:43It’s wild how something so complex is just... normal to us now. Like breathing. We don’t think about oxygen molecules, but we need them. Same with these names. They’re the invisible scaffolding keeping us safe.

Ali Bradshaw

December 9, 2025 AT 09:14Love how the suffixes work. -prazole, -tinib, -siran. It’s like drug family trees. Makes me feel smarter just knowing the pattern. Still can’t pronounce tofacitinib though 😅

an mo

December 10, 2025 AT 14:45Of course the USAN and WHO are ‘harmonizing’ names-while Big Pharma still charges $1,200 for a 30-day supply of a drug invented in a lab funded by taxpayer money. This naming system? Just another pretty lie to make us feel safe while they profit.

aditya dixit

December 10, 2025 AT 16:32The precision in naming conventions reflects the rigor required in pharmacology. A single misplaced letter or phonetic similarity can lead to catastrophic outcomes. The systematic rejection of 30% of proposed names is not bureaucratic overreach-it is a necessary safeguard.

Annie Grajewski

December 11, 2025 AT 05:19so like… the brand name is just the drug’s influencer version? like ‘Prozac’ is the one with the good lighting and the caption ‘feeling better since 1988’ 😂

Mark Ziegenbein

December 12, 2025 AT 13:56Let’s be real-the entire system is a masterpiece of bureaucratic elegance masked as scientific necessity. The chemical name? A linguistic monument to human precision. The generic? The democratic compromise. The brand? Capitalism’s glittering crown. And yet, we’re told it’s all about safety. But what if safety is just the marketing slogan for control? Who decides what ‘safe’ means? Who funds the AI that checks the names? Who profits from the confusion? The system doesn’t protect you-it protects the system.

Norene Fulwiler

December 12, 2025 AT 22:57My grandma in rural Texas used to call all her pills ‘the blue ones’ or ‘the little round ones.’ She never knew the names, but she never mixed them up. Sometimes, human memory beats the best-named drug in the world.

William Chin

December 14, 2025 AT 10:50While I appreciate the technical accuracy of this exposition, I must express my profound concern regarding the potential for misinterpretation among non-English-speaking populations. The Latin-based nomenclature, while scientifically rigorous, may inadvertently exacerbate disparities in healthcare accessibility for marginalized linguistic communities.

Ada Maklagina

December 14, 2025 AT 18:56generic is cheaper but sometimes the color is off and I panic for a week thinking I got the wrong meds. then i check the bottle. always the same. but still. anxiety.

Katie Allan

December 15, 2025 AT 11:50It’s beautiful how a system built for science ends up helping people who don’t even know it exists. No fanfare. No ads. Just a quiet, smart structure keeping millions from harm. We don’t celebrate these systems enough.

Deborah Jacobs

December 16, 2025 AT 08:10I used to think drug names were just corporate nonsense-until my dad had a bad reaction to something that sounded like another drug. Turned out it was the brand name that tripped up the nurse. Now I memorize the generic. It’s the only thing that doesn’t lie.

James Moore

December 17, 2025 AT 13:46Let’s not pretend this is just about safety-it’s about power. The WHO, the FDA, the USAN Council-they’re not neutral arbiters. They’re gatekeepers. They decide what gets a name, what gets rejected, what gets marketed. And who gets to speak up? Big Pharma. The patient? They’re just supposed to swallow it. Literally. And smile. Meanwhile, the AI that checks names? Trained on data from countries that don’t even have pharmacies in half their towns. This isn’t science. It’s a colonial legacy dressed in lab coats.