When your urine looks foamy or bubbly after you pee, it’s easy to brush it off as just normal. But if it happens often, especially with swelling in your ankles, puffy eyes, or unexplained fatigue, it could be your kidneys sending a warning signal. That signal is called proteinuria-too much protein leaking into your urine. It’s not a disease on its own, but it’s one of the clearest early signs that your kidneys are under stress or damaged. And catching it early can stop serious kidney problems before they start.

What Proteinuria Really Means

Your kidneys are like fine filters. They keep proteins-especially albumin-where they belong: in your blood. These proteins help with healing, fluid balance, and muscle function. Healthy kidneys let through less than 150 milligrams of protein per day. When that number climbs above 30 mg/g of creatinine in a spot urine test (called UACR), you’ve got proteinuria. That’s not normal. It means the filters in your kidneys, called glomeruli, are damaged or clogged. They’re letting protein slip through, like a sieve with holes.

Proteinuria shows up in three main ways: transient, orthostatic, or persistent. Transient means it’s temporary-happens after a fever, intense workout, or extreme stress. Orthostatic proteinuria shows up only when you’re standing, not when you’re lying down. It’s common in teens and young adults and usually harmless. But persistent proteinuria? That’s the red flag. It doesn’t go away. And it’s almost always tied to something deeper: diabetes, high blood pressure, or kidney inflammation.

How Doctors Detect It

Most people don’t feel proteinuria until it’s advanced. That’s why testing matters. The first step is usually a dipstick test-your doctor puts a special strip in your urine sample. It changes color if protein is present. But this test isn’t perfect. It can miss early or low levels of protein. That’s why confirmation is key.

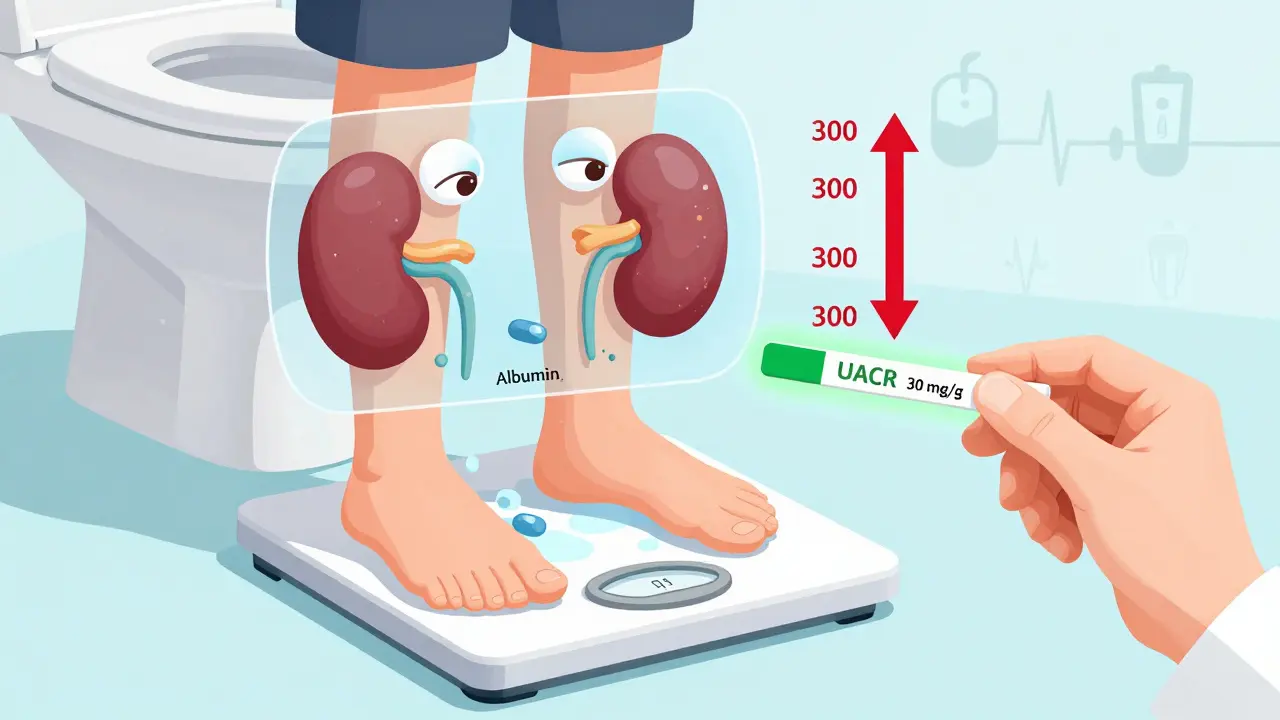

The gold standard isn’t a 24-hour urine collection anymore. Too many people forget to collect all their urine, or the container leaks. Instead, doctors now use the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR). You give one sample, and they measure how much albumin (the main protein) is in your urine compared to creatinine (a waste product your body makes at a steady rate). A UACR above 30 mg/g means you have proteinuria. Above 300 mg/g? That’s severe. And if you’re diabetic or hypertensive, even a UACR above 30 should trigger action.

Some labs use a more advanced test called urine protein electrophoresis. It tells you what kind of protein is leaking. Is it albumin? That’s usually kidney-related. Is it Bence-Jones protein? That could point to multiple myeloma. These details help doctors zero in on the cause.

What Causes Proteinuria?

Not all proteinuria is the same. The cause changes how you treat it.

- Diabetic nephropathy causes about 40% of persistent cases. High blood sugar slowly damages the kidney filters over years. If you’ve had diabetes for more than 10 years, you’re at high risk.

- High blood pressure is behind 25%. Constant pressure on the tiny blood vessels in your kidneys wears them down.

- Glomerulonephritis (inflammation of the kidney filters) accounts for 15%. This can be from infections, autoimmune diseases like lupus, or unknown causes.

- Preeclampsia during pregnancy can cause sudden proteinuria. It’s dangerous for both mom and baby and needs immediate care.

- Multiple myeloma and amyloidosis are rarer but serious. They flood your blood with abnormal proteins that overwhelm the kidneys.

Even heart disease can cause proteinuria. If your heart isn’t pumping well, your kidneys don’t get enough blood. They respond by leaking protein. It’s a domino effect.

What You Might Notice (and What You Won’t)

Here’s the scary part: early proteinuria often has no symptoms at all. About 70% of people with mild proteinuria feel completely fine. That’s why screening is so important-if you have diabetes, high blood pressure, or a family history of kidney disease, you should get tested every year.

When proteinuria gets worse-over 1,000 mg per day-you start to see signs:

- Foamy, bubbly urine (85% of people notice this)

- Swelling in feet, ankles, hands, or face (75%)

- Unexplained tiredness (60%)

- More frequent urination, especially at night (45%)

- Nausea or loss of appetite (25%)

If protein loss hits 3,500 mg/day or more, you might develop nephrotic syndrome. That means your blood albumin drops below 3 g/dL, your cholesterol skyrockets, and swelling becomes severe. This is a medical emergency.

How to Reduce Kidney Damage

Reducing proteinuria isn’t just about treating symptoms-it’s about saving your kidneys. Every gram of protein you stop losing saves your kidney function.

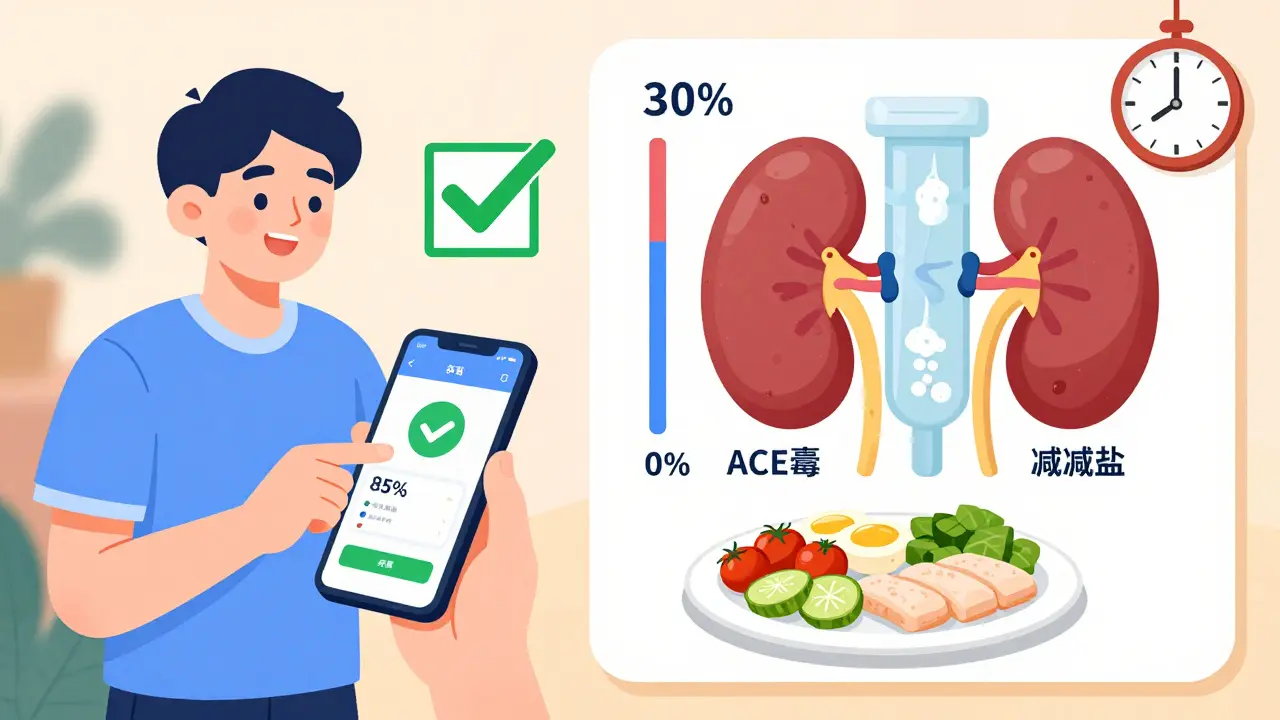

For people with diabetes or high blood pressure, two classes of drugs are game-changers: ACE inhibitors and ARBs. These blood pressure meds don’t just lower pressure-they directly protect the kidney filters. Studies show they can cut proteinuria by 30-50%. If you’re on one and still have high protein levels, your doctor might add an SGLT2 inhibitor like canagliflozin. These diabetes drugs also reduce proteinuria by 30-40% and slow kidney decline.

Newer drugs like finerenone (a non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist) are showing promise too. In trials, it reduced proteinuria by 32% in diabetic kidney disease. It’s not yet first-line everywhere, but it’s becoming more common.

Lifestyle changes matter just as much:

- Lower protein intake: Aim for 0.6-0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day. Too much protein forces your kidneys to work harder. A renal dietitian can help you plan meals without cutting out nutrition.

- Control blood pressure: Target below 130/80 mmHg. Every 10 mmHg drop in systolic pressure can reduce proteinuria by 10-20%.

- Reduce salt: Over 2,300 mg per day worsens swelling and raises pressure. Stick to whole foods, avoid processed snacks.

- Quit smoking: Smoking speeds up kidney damage. It’s one of the biggest modifiable risks.

For autoimmune causes like lupus nephritis, immunosuppressants like corticosteroids or rituximab can bring proteinuria into remission in 60-70% of cases. But these come with side effects, so they’re only used when needed.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

Proteinuria doesn’t fix itself. You need to track it. If you’re stable, check your UACR every 6 months. If you’ve just started treatment, check every 1-3 months. A good sign? A 30% drop in proteinuria within 3 months. That’s linked to a 30% lower risk of kidney failure down the road.

Patients who learn to check their own urine for foaminess and track swelling at home catch worsening symptoms 25% earlier than those who wait for doctor visits. Simple tools like a smartphone app for urine analysis (new ones now have 85% accuracy) are starting to help people monitor between appointments.

What’s Next in Research

The future of proteinuria care is getting smarter. Researchers are now looking at new biomarkers in urine-like TNF receptor-1-to predict who’s at highest risk of fast kidney decline. In trials, this marker can spot danger before protein levels even rise.

There’s also excitement around targeted therapies. For example, bardoxolone methyl, tested in Alport syndrome (a rare genetic kidney disease), cut proteinuria by 35%. It’s not approved everywhere yet, but it shows we’re moving toward personalized treatment.

And the market is growing. The global test market for proteinuria is expected to hit $2.1 billion by 2027. Why? Because more people have diabetes. More people are living longer with high blood pressure. And we’re finally learning: catching proteinuria early saves lives.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can proteinuria go away on its own?

Yes-but only if it’s transient. If it’s caused by a fever, intense exercise, or stress, it usually disappears once the trigger is gone. But if proteinuria lasts more than a few weeks or keeps coming back, it’s likely linked to an underlying condition like diabetes or high blood pressure. That won’t fix itself. Left untreated, it can lead to permanent kidney damage.

Is foamy urine always a sign of proteinuria?

Not always. Sometimes, foamy urine happens because of a fast urine stream or dehydration. But if the foam is thick, stays for minutes, and keeps happening-even when you’re not rushing to the toilet-it’s likely protein. A simple urine test can confirm. Don’t assume it’s nothing.

Do I need to stop eating protein if I have proteinuria?

No-you don’t need to cut protein entirely. But you do need to reduce it to the right level: 0.6-0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day. Too little protein can cause muscle loss and weakness. Too much overworks your kidneys. A renal dietitian can help you find the balance. Focus on high-quality protein sources like eggs, fish, and lean meats, and avoid processed meats and excessive dairy.

Can I test for proteinuria at home?

There are now FDA-cleared home test strips and smartphone apps that analyze urine color and foam patterns with about 85% accuracy. They’re not replacements for lab tests, but they’re great for tracking changes between doctor visits. If you notice increasing foam or swelling, don’t wait-get a lab test. Early detection is your best defense.

If I have proteinuria, will I need dialysis?

Not if you act early. Studies show that reducing proteinuria by 30% or more within the first 3 months of treatment cuts your risk of needing dialysis by half. The key is catching it early and sticking to treatment-meds, diet, blood pressure control. Many people with proteinuria never reach kidney failure. It’s not a death sentence-it’s a warning sign you can respond to.

Next Steps

If you’ve been told you have proteinuria, don’t panic. But don’t ignore it either. Start with three actions:

- Get a confirmed UACR test if you haven’t already.

- Ask your doctor if you’re on an ACE inhibitor or ARB-and if not, why not?

- See a renal dietitian to adjust your protein and salt intake.

And if you’re diabetic or hypertensive, make sure you’re getting tested for proteinuria every year-even if you feel fine. Your kidneys can’t talk. But they leave clues. Learn to read them.