Every year, Americans pay more than three times what people in other developed countries pay for the exact same prescription drugs. It doesn’t matter if the pill was made in New Jersey or Switzerland - if you’re filling a prescription in the U.S., you’re likely paying far more than someone in Germany, Canada, or the UK. And it’s not just a few expensive drugs. This is the norm across hundreds of medications, from insulin to cancer treatments to rare disease therapies.

How Did We Get Here?

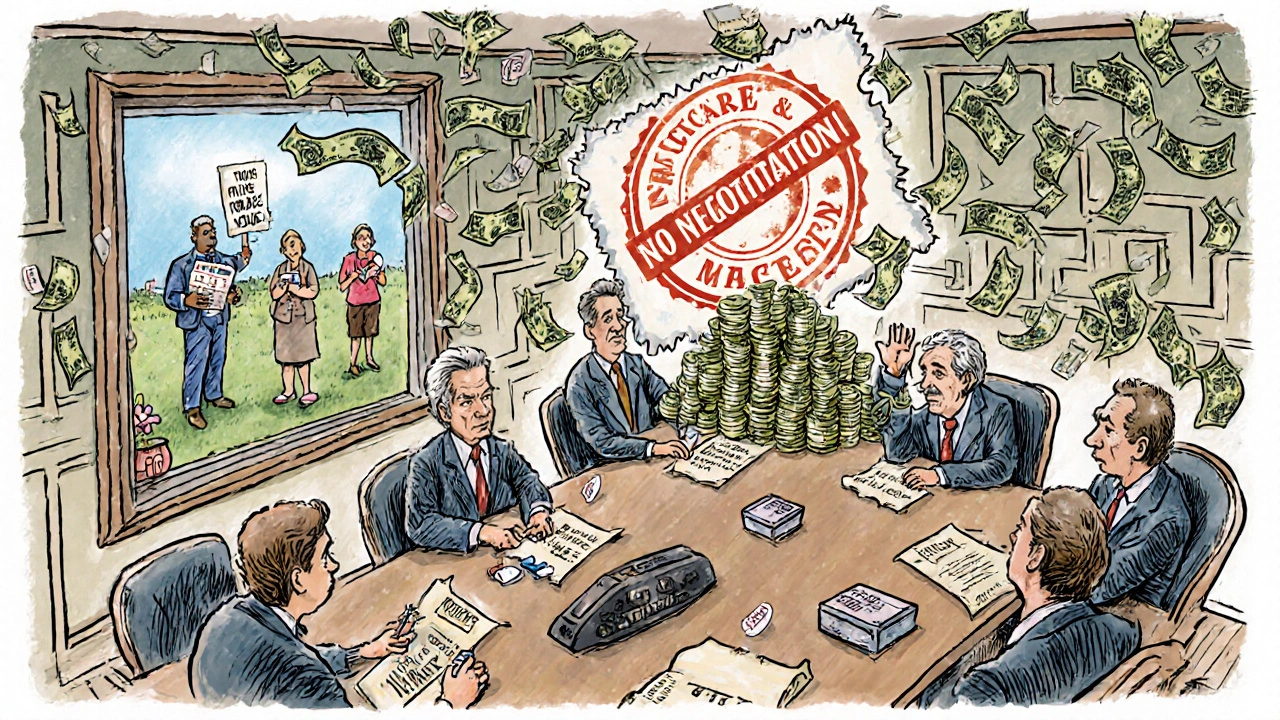

The root of the problem isn’t one single decision - it’s a system built over decades. In 2003, Congress passed the Medicare Modernization Act, which created Medicare Part D, the program that helps seniors pay for prescriptions. But there was a catch: the law explicitly banned Medicare from negotiating drug prices directly with manufacturers. That meant the government, which buys drugs for over 60 million people, couldn’t use its massive buying power to get lower prices. Instead, it had to accept whatever price drug companies set. Other countries don’t do this. Germany, France, and Canada all have government agencies that sit down with drugmakers and say, “This is what we’re willing to pay.” If the company doesn’t agree, the drug doesn’t get covered. In the U.S., there’s no such negotiation. Drugmakers set the list price, and then the real game begins - with Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), insurers, and middlemen juggling rebates, discounts, and hidden fees.Who Really Controls the Price?

You might think your pharmacy or insurance company sets the price. But the real power lies with PBMs - companies like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx. They were originally created to help insurers save money by negotiating discounts with drugmakers. But over time, they changed. Now, many PBMs are owned by the same big corporations that run insurers and pharmacies. That creates a conflict of interest. Here’s how it works: A drugmaker raises the list price of a medication. The PBM demands a bigger rebate from the manufacturer to include the drug on its formulary (the list of covered drugs). The higher the list price, the bigger the rebate. So even if the final price you pay at the pharmacy goes down slightly, the drugmaker makes more money, and the PBM makes more money. The patient? They’re still stuck with a high out-of-pocket cost, especially if they haven’t met their deductible. This system rewards high prices, not low ones. It’s why the same drug - Galzin for Wilson’s disease - costs $88,800 a year in the U.S., but only $1,400 in the UK. The drug is identical. The factory is the same. The only difference? The U.S. system lets companies charge whatever they want.The Profit Machine

The U.S. accounts for less than 5% of the world’s population, but generates about 75% of the global pharmaceutical industry’s profits. That’s not an accident. It’s the result of a business model built on price autonomy. Companies argue they need high prices to fund research and development. But the numbers tell a different story. In 2024, the net price of prescription drugs in the U.S. jumped 11.4% - more than double the 4.9% increase from the year before. Much of that growth came from new obesity and diabetes drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy. These drugs cost over $1,000 a month on the list price. But in September 2025, the White House announced deals with manufacturers that cut Ozempic’s price from $1,000 to $350 a month and Wegovy from $1,350 to $350. That’s a huge drop. But here’s the catch: those were voluntary deals, not a systemic fix. And they only apply to Medicare. Millions of people with private insurance still pay the full price. Meanwhile, Senator Bernie Sanders’ September 2025 report found that 688 prescription drugs increased in price since President Trump took office - despite repeated promises to lower costs. In fact, 87 drugs saw price hikes of 8% or more after Trump sent letters to drugmakers asking them to lower prices. That’s not a coincidence. It’s how the system works.

The Inflation Reduction Act - A Start, But Not Enough

In 2022, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act. For the first time, Medicare was allowed to negotiate prices for a small number of high-cost drugs. In 2026, ten drugs will be covered under this program. The government expects to save $1.5 billion in out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries. That’s meaningful. But it’s a drop in the bucket. The law also introduced a cap on out-of-pocket drug costs for Medicare Part D users - $2,000 per year. Before this, some seniors paid over $7,000 a year just for their prescriptions. That cap will be life-changing for many. But it doesn’t help people with private insurance. And it doesn’t stop drugmakers from raising prices next year. Worse, the 2025 budget reconciliation bill (HR 1) weakened the negotiation program. According to KFF, it could increase Medicare spending by at least $5 billion. That means even the small progress made could be undone.What About the Rest of the World?

Other countries don’t have this problem because they don’t let drugmakers run the show. In the UK, the National Health Service negotiates prices. In Canada, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board sets price limits. In Germany, manufacturers must prove their drug is “new and improved” before they can charge more than existing treatments. The U.S. is the only developed country that doesn’t regulate drug prices at all. No price caps. No negotiation. No transparency. Just a free-for-all. And the cost isn’t just financial. People are skipping doses. Cutting pills in half. Choosing between insulin and rent. The White House and HHS have acknowledged this. CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure said the $2,000 cap will be “life-changing.” But she’s talking about Medicare. What about the 18.5 million non-Medicare patients who could face higher costs under Project 2025’s proposed drug plan? What about the millions who don’t qualify for any assistance?

Destiny Annamaria

November 19, 2025 AT 13:36Y’all ever try to get insulin without insurance? I’m not even joking - I had to choose between my meds and my phone bill last month. My mom’s diabetic and we’re just barely hanging on. This system is designed to break people like us.

Ron and Gill Day

November 20, 2025 AT 05:30Oh please. If you didn’t want to pay $1000 for Ozempic, maybe you shouldn’t have eaten a whole pizza every night. This isn’t a right - it’s a privilege earned by not being lazy.

Alyssa Torres

November 21, 2025 AT 16:39I cried reading this. My cousin died because she skipped her cancer meds to pay rent. This isn’t capitalism - it’s cruelty dressed up as ‘market efficiency.’ We are literally letting people die so CEOs can buy third yachts. Wake up, America.

Summer Joy

November 21, 2025 AT 20:57THEY’RE ALL IN IT TOGETHER!! PBMs + pharma + insurers - it’s a triangle of evil!! 😭💸 I saw a post from a girl in Ohio who had to sell her car for insulin. AND THE GOVERNMENT IS JUST SITTING THERE!! 😭

Aruna Urban Planner

November 22, 2025 AT 04:41The structural inefficiencies in the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain are exacerbated by the absence of centralized price-setting mechanisms. Comparative effectiveness research, as implemented in NICE, would yield significant welfare gains. The rent-seeking behavior of PBMs represents a classic principal-agent problem with asymmetric information.

Nicole Ziegler

November 23, 2025 AT 22:25same. just got my prescription and my copay went from $20 to $180 overnight. 🤡 why is this even legal?

Bharat Alasandi

November 24, 2025 AT 17:51in india we pay like $5 for same insulin. no joke. here in us its like paying for a new car every year just to stay alive. crazy system

Kristi Bennardo

November 25, 2025 AT 23:08This is a national disgrace. The pharmaceutical industry has corrupted every branch of government through campaign contributions and revolving-door appointments. This is not capitalism - it’s corporatist fascism, and it must be dismantled immediately.

Shiv Karan Singh

November 27, 2025 AT 17:37lol you think this is bad? wait till the aliens start selling the drugs. they’re already controlling the patents. I saw a guy on YouTube say the FDA is just a front for Big Pharma. And the moon landing? Fake. So is your ‘cheap insulin’ 😏

Ravi boy

November 28, 2025 AT 01:14bro i live in delhi and my dad gets same medicine for 500 rupees like 6 bucks. here in usa people act like its magic or something. its just pills. why so expensive? i dont get it

Liam Strachan

November 28, 2025 AT 06:53It’s fascinating how the U.S. has managed to create a system where innovation is financially rewarded but access is treated as a luxury. Other countries manage to balance both - perhaps we just need to stop treating healthcare like a stock market.

Gerald Cheruiyot

November 29, 2025 AT 19:24It’s not about the cost of production. It’s about the cost of monopoly. Patents were meant to incentivize innovation, not to create permanent profit monopolies. We’ve lost sight of the original intent. The system is broken because we stopped asking: who is this for?

Michael Fessler

November 30, 2025 AT 22:28the pmb thing is wild - they get paid based on the list price so they have zero incentive to lower it. even if you get a discount the list price goes up so they make more. it’s like a casino where the house always wins. and no one knows the real price till you get to the counter

daniel lopez

December 1, 2025 AT 03:04Obamacare was a trap. The government knew this would happen. They let Big Pharma write the laws. Then they made us pay for it with our taxes. This is all part of the New World Order. They want you dependent. They want you weak. Don’t trust the ‘solution’ - it’s just another cage.

Nosipho Mbambo

December 3, 2025 AT 02:43...this is... just... so... deeply... wrong... I... I... can't... even... breathe... right now... 😭😭😭